Doireann Ní Ghríofa, Lies, Dedalus Press

This one is in English as I try to write my book reviews in the language of the book I read. Since my Irish is still – and might remain – very rudimentary, English will have to do.

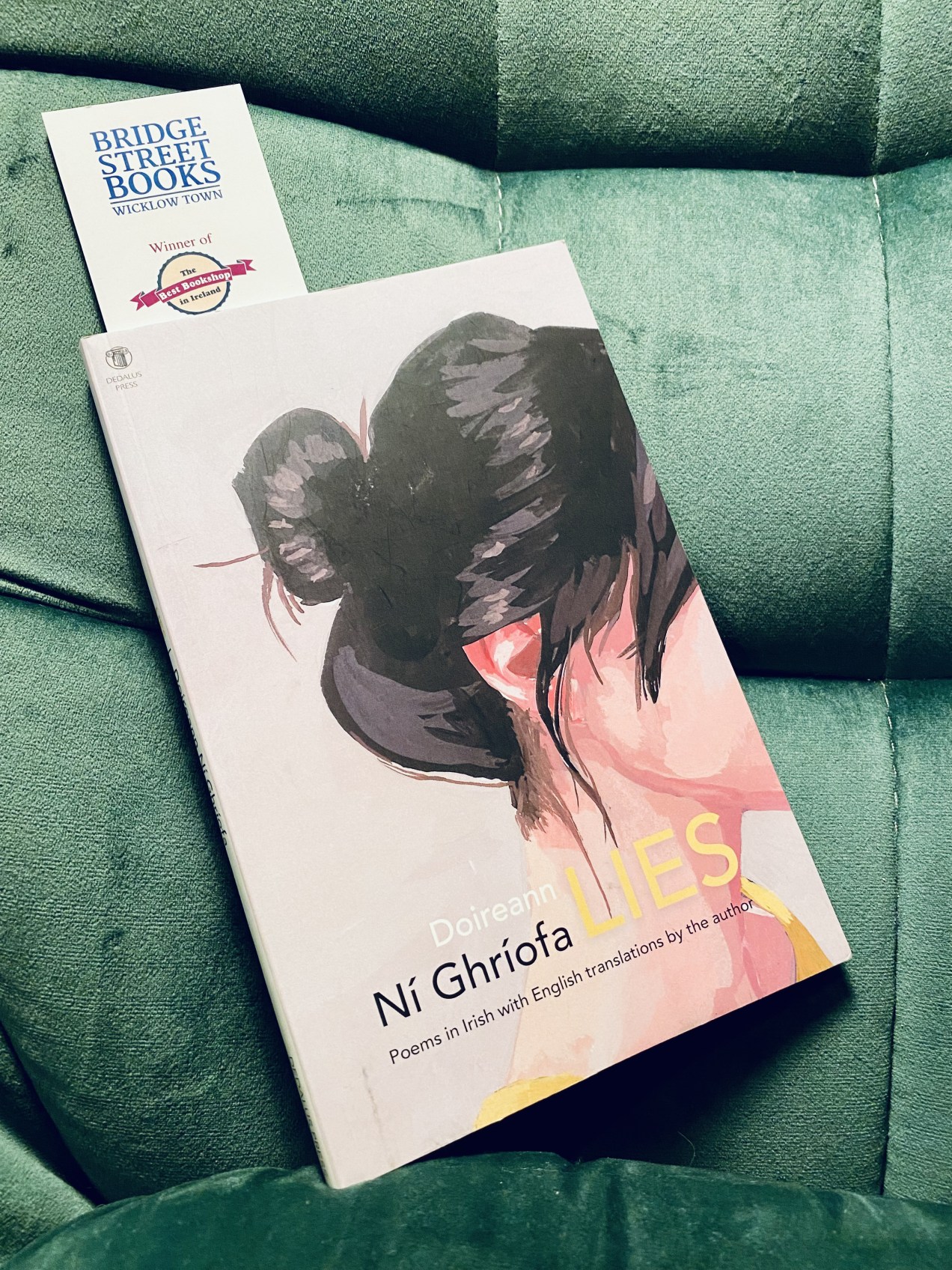

When did I really decide to take up that walk uphill that is trying to learn the Irish language? If it comes down to it, I’d say it was that road trip to the west of Ireland in 2022. You might be able to distil it into a few special moments that trickled into my brain, clouded my better judgement and made me take decisions that were clearly under some influence. So after being infused by picturesque landscape, magical light breaking through clouds, uplifting „seisiún“ music and altogether loveliness of the people, I stumbled into the little gem that is Bridge Street Books in Wicklow (btw the winner of Best Bookshop in Ireland 2022, as I was informed by the bookmark I later received).

I automatically went to the poetry section that was quite sizeable in proportion to the shop and discovered not only Irish poetry, but, to my delight: Poems in Irish with English translations by the author. Maybe, I thought, I had also been given a share of that famous ‚luck of the Irish‘.

The cover drew me in, that exposed neck, the title ‚Lies’ overlapping the skin with yellow capital letters…

Fast forward to 2024, after useless hours on Duolingo (get your grammar straightened out, please and stop mixing the dialects, thank you), I finally found a great online Irish class by SKSK Königswinter, taught by amazing Chris Fischer, who can literally break the rules down to its essentials and provides materials as easy and clear as they get. I promise to end the advertisement here, but I do have to add that they can be highly recommended for celtic culture, language and music.

So here I am, starting to understand a tiny little bit of that language where you are rather accompanied by feelings than having them inhabit (and control) you, where spiders were named after „fierce little stags“ and the word for cousin („col“) indicates the degree of relationship by stating the number of people that are linked to/ or biologically separated by this relationship (in the case of the first cousin, that is four, „ceathrar“: person – parent – parent’s sibling – parent’s sibling’s child). Yes, it’s complicated and beautiful.

Now that at least the sound of the language the poems have originally been written in is a bit more familiar to me, I found the time to comment on my resonance to Doireann Ní Ghríofa’s poems.

The book starts with thanks to her parents (in Irish) and a quote by Lucie Brock-Broido encouraging us not to be afraid to tell the truth, even if it’s a lie. What is the true poem, if written by the same author – the original Irish version or the English one as well? Is the English translation by the author less of a lie than any other translation would be? And can any reader who is more fluent in one of those languages even come close to a decision? What the ‚true‘ Irish language is amongst the dialects, older and more modern words – we won’t even go there!

In „An Chéad Choinne, Sráid Azul/ First Date on Azul Street“, the tone is set, we get a first impression of the swiftness of moments, of truth:

„Imíonn gal is deatach le haer/

Our smoke and steam rise into the sky“.

The journey of butterflies all the way to Mexico leads to the Aztec people leads to souls of the dead leads to

„wounds turning to red wings/

a gcneácha

tiontaithe ina sciatháin dhearga“.

Swiftness of images, of words, of associations:

„Nuair a osclaím mo bhéal,

eitlíonn mo theanga uaim ar an ngaoth/

When I open

my mouth, my tongue flies away.“

Is it the swiftness that bears the lie? The fact truth can never be truly grasped?

In „Glaoch/ Call“ the author implies the loss of true connection through digitisation, when she states that

„Now that our computers call each other,

I can’t

press your voice to my ear/

I réimse na ríomhairí,

ní thi liom

do ghuth a bhrú níos gaire do mo chluas“.

The field of computers does not make it into the English version.

And when Doireann Ní Ghríofa refers to two rabbits in a Spanish proverb (or of Spanish language?) that forms the same title for both versions of the poem „Dos Conejos“ – you start to chase both rabbits but end up lost in the same rabbit hole. I guess I just can’t make more than two ends meet at once, if even that.

The confusion is not lifted in the slightest bit when I turn the page to find the poem „Le Tatú a Bhaint/ Tattoo Removal“ to be even set differently, with the Irish one consisting of three stanzas while the English version is stretched to four. And a failed tattoo removal leads to me now failing to quote one single line in both languages that align and speak for the poem – I feel a bit lost in translation or did I just sink in like the letters that could not be removed? „Mé féin is tú féin“.

And then the ode like poem „Tinfoil/ Scragall Stáin“ makes me chuckle quite a bit and realise that playfulness might get me closer to the truth of what language tries to convey, not trying to nail it down word by word but rather playing it by ear:

„Oh look, Dad, the river’s smooth as tin foil!/

A thiarcais, tá an abhainn chomh slíomach le scragall stáin“.

The jigsaw of birth, gaps of suburbia, meditations on friendship and mashed potatoes, swapping nightclub sounds to the „buzzing hum/ dhúisíonn“ of a noctuary dishwasher, reflections on homework, genealogy under fridge magnets, sunken ships and loss – loss that lingers:

„déanta di siúd

a d’fhan, is

a d’imigh léi

i bhfaiteadh na súl/

a dress

for a girl who came

and left

too soon“

(…)

„Fásann an liathróid olla

i mo lámh: lúbtha, laich, lán./

I hold this soft unravelment as it grows,

and O, it grows, this un-wound wool. It grows. Dull. Full.“

The poet stays true to the idea that showing is more than telling – and existential experiences are reflected in every-day objects and activities. Different languages each call for their own image, sound and form. It seems like you can chase two rabbits at once after all.

And then she finishes the book with such a funny Irish curse you do not miss any blessings.

Doireann Ní Ghríofa, if your lies are always this true, please provide us with many more, le do thoil.